The woven home and fashion fabrics of Turkish textiles house Kutnia, based in the ancient, atmospheric city of Gaziantep in the southwestern region of Anatolia, are extraordinarily colourful and lustrous. Company descriptions of the latest home collections, encompassing a panoply of products including bedspreads, cushions and kimonos, are peppered with evocative words referencing their characteristically stunning colourways.

One particularly vibrant collection, Jewel, features stripes of blazing ‘ruby’, electric ‘sapphire’, ‘gold’ and a pasteltoned ‘Turkish pink’. Another one, called Spice, boasts richly hued stripes linked to such words as ‘pomegranate’ (think the glossy red arils, used to make grenadine, inside the fruit), ‘aubergine’, ‘damson’ and ‘thyme’ (a cooler blue). ‘Pistachio’ and ‘lemon’ are just two shades describing the luminously citrus-toned Garden collection.

Such words highlight a key aspect of Kutnia—how localised culture shapes the brand. Olives and pistachios grow in abundance in this fertile region, and Gaziantep is part of UNESCO’s Creative Cities Network in recognition of its outstanding cuisine, influenced by a rich blend of cultures that have left their mark, from Byzantium to the Ottoman Empire that superseded it.

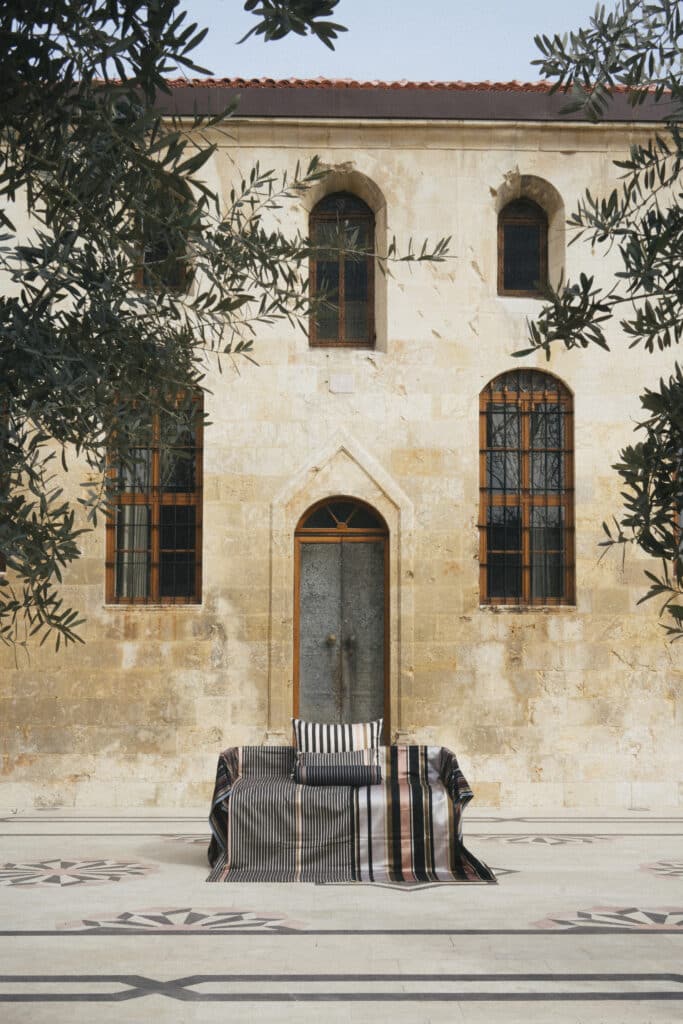

The Spice collection is inspired by Gaziantep’s traditional food and spice markets—easily spotted, thanks to the strings of fiery orange, dried tomatoes and chilli peppers hanging above their stalls and baskets brimming with herbs and flower heads. The city boasts ageold limestone architecture, cobbled streets and home-grown crafts such as coppersmithing, fabricated in the city’s Old Bazaar. These aspects inspire other Kutnia fabrics, some of which have more mellow, neutral colourways.

The company was founded in 2017 and is now headed up by Jülide Konukoğlu. Its fabrics spring from an Anatolian weaving tradition dating from the 16th century called kutnu—a word derived from ku t ’n, meaning cotton in Arabic—which features longitudinal stripes. Kutnu was originally made by combining 60% silk or floss silk (the warp) and 40% cotton (the weft). Kutnia pays homage to some of the sixty named patterns of kutnu, including the imminent launch of a Heritage collection, inspired by 17th-century motifs.

Located at a strategically important position at the crossroads of the Silk Road, Gaziantep exported kutnu across the Ottoman empire, and the luxurious fabric with its distinctive sheen was prized by the Ottoman court. Kutnia, whose HQ occupies a handsome, restored mansion in Gaziantep’s picturesque neighbourhood

of Bey Mahallesi, was set up to preserve a weaving technique on the brink of dying out. Circa 1900, around 5,000 hand looms fabricating kutnu textiles and kilims thrummed in houses all over Gaziantep. By the late 20th century, globalisation and mass production of textiles had threatened the survival of this craft— latterly perceived as labour-intensive, requiring exacting, expensive quality control and outmoded.

When Konukoğlu established Kutnia, she sourced 19th-century semi-automatic looms in her quest to fabricate kutnu fabrics authentically. The brand also has a collection of antique kutnu fabrics—some plain, some with ikat patterns—which sta can reference.

‘We acquired our looms in Turkey, all of which had to be disassembled then meticulously reassembled,’ says Ms Sevim, Kutnia’s general manager. ‘The first looms we found measured 120 cm but we later bought ones measuring 200 cm. Different looms are needed depending on the width of the fabric we weave.’

Kutnia was placed in grave danger when the recent catastrophic earthquake struck Turkey and Syria; its epicentre was only 37 km away from Gaziantep. Fortunately, the tight-knit Kutnia team based in Gaziantep were unharmed and the factory’s looms were largely undamaged. Within two weeks, the company was fully operational again, although normalising the business after the earthquake has been challenging.

Fabricating kutnu textiles is extraordinarily complex. It takes up to two months for Kutnia’s designers and research and development team to originate a new design, and highly specialist craftspeople are responsible for each stage of fabrication.

‘Our master weaver has fifty years’ experience working with kutnu fabric,’ says Ms Sevim. ‘Our factory chief did an MA in weaving and is extremely skilled at weaving kutnu fabrics. Initially, she worked as a consultant and later joined our team. We also hire young apprentices. After they’ve worked in di erent departments observing various stages of weaving, they learn hands-on weaving on sample machines, overseen by our master weaver at all stages of the weaving process.’

Kutnia sources ready-dyed yarns that come with an Oeko-Tex certification, indicating that they don’t harm the environment or humans during the production process. Their hues are found on standardised colour-matching system Pantone and are colour-fast, ensuring there are no unwanted variations in the fabrics’ colours.

The first stage of production involves separating the threads wound round spools, a process called disassembly. To complete this, the warp is wrapped around rollers attached to the looms. Each thread is then wound around a four-sided wooden frame known as a devere, to prepare the warp. To prevent threads from wobbling as they unwind from the spools, the latter are stabilised by anchoring them in sand on the floor—an ancient practice.

The warp threads are then attached to the looms; sometimes there are threads on the looms already, in which case the new threads are tied to the old ones (a method called bedris). This semi hand-weaving process is kickstarted when the weft, on spools above the loom, is dropped on to the warp by the weaver.

Kutnia’s hand-crafted fabrics are made using three weaving methods—twill, sateen and plain—to meet the varying requirements of producing clothing, accessories and home textiles, including for upholstery and curtains. The weight and finish of the fabric produced and how it’s used in production is obtained by using different yarn numbers and densities and widths of 100 cm or 140 cm. The required properties of each fabric type are extensively tested in a laboratory to ensure quality and suitability.

Once woven, the fabrics are washed to check for shrinkage, with two final stages of quality control guaranteeing every bolt of fabric produced meets Kutnia’s exacting standards. A 50-metre length of fabric takes eight weeks to produce, including the bedris process, weaving, quality control and washing.

Quality and a commitment to the art of weaving is at the heart of this remarkable, highly specialist process, as evidenced by the signature of the master weaver who wove the fabric, visible on the selvedge of all Kutnia fabrics.

The goal is to preserve the ancient craft of weaving kutnu; and Kutnia has done this by modernising the fabric and making it suitable for contemporary use. According to Ms Sevim: ‘Our objective is to create a product fit for contemporary living while remaining true and faithful to kutnu’s DNA.’